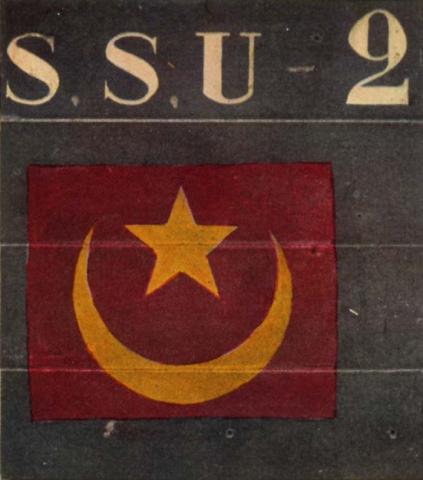

Section Two (SSU 2) – Part II

- When

- WWI

- Where

- Western Front, France

VI

IN THE MIDST OF THE BATTLE OF VERDUN

Verdun, May, 1916

For two weeks the Section worked night and day with scarcely time for sleeping and eating, but when our labor slowed up, the men had time to catch up lost sleep. Sleeping quarters were in the loft of a barn between the lane, which was the entrance to the estate, and the chàteau. Due partly to the rainy and damp weather, and the hard work, many of the fellows were on the verge of illness, and at night the loft sounded very much like a consumptive retreat. Every available space was occupied by the sleepers, and a few of the Section found accommodations in a couple of small buildings in the rear of the château, on the edge of the park, a small shack used for storing fishing paraphernalia, and another near by which gave shelter from nothing but the rain and snow. One of the strangest things in that part of the estate was an "Old Town" canoe with a paddle made from a broken airplane propeller which belonged to an aviator from the flying field on the top of the hill. From time to time several of our fellows went canoeing in it on the Meuse which flowed close by.

The meals were served in a farmhouse on the main road, at the head of the lane, these eating quarters being the worst part of our life there. The owners still hung on, though they had been ordered to leave long before, and their presence did not add to the pleasures of the spot. The dining-room was the kitchen and living-room, and at eating times was jammed full of hungry Americans, Frenchmen who were trying to buy wine of the Madame, and the Madame's family of eight very dirty children. A table in the centre of the room was reserved for the Section, though there was scarcely place for half the men.

Plates and table hardware were seldom washed, and it often happened that nothing was cleaned for several meals, while to add to the unpleasantness of the situation, hostlers kept opening and closing a door which was the entrance to the foulest stable imaginable. Possibly there would have been a general "kick" on the part of the Section if it had not been for the fact that we were worn out from the hard work and long hours of driving, which sometimes amounted to over 200 kilometres per day per car.

The cars too were in a sad state and most of them fit for the "graveyard" in Paris. On March 4, one new car and two overhauled ones came out from Paris, and two days later, two more arrived. That night orders were received at eight o'clock to move to Vadelaincourt at once.

Heavy fighting was going on then between Hill 304 and the Meuse and there was such a stream of wounded pouring into Vadelaincourt that the hospital was swamped. There was no room at the château for the freshly operated-upon men, so they were taken at once to other hospitals in the direction of Bar-le-Duc and Révigny. One French sanitary Section and two British Sections had been doing the work, but there were too many wounded for these outfits and Section Two was called upon to help.

The majority of our cars arrived at the chàteau by 10 o'clock, and after throwing duffle-bags and blanket rolls into a barn, the men set to work evacuating and worked steadily at their task for nearly three days with no sleep. The first night every car evacuated to Révigny over the main Bar-le-Duc-Verdun road, which was a continual stretch of holes and ruts, so that no car could go more than fifteen miles an hour, due to the roughness of the road and the dense traffic. After the first four days the French Section and one of the British Sections left, the whole work now falling to our Section Two and to English Section Two. There was still plenty of it, but it could be run more systematically.

AT CAMP

The Section slept in its cars, which were parked on the side of the road near the hospital, and our kitchen was established in one of the rooms of a farmhouse, very close to a barn and a huge heap of manure. The dining-room, which was a sort of "lean-to" against the side of the house, was made of blankets and canvas and not very watertight. For three weeks we lived this way, and then, during a spell of good weather, erected a tent (borrowed from the head French military doctor, who was a very good sort) in a lot across the road from the aviation field. However, most of the Section by that time had found sleeping-quarters in two rat-infested barns, everybody however, taking the unpleasant life philosophically. One of the barns was also occupied by the English Section, and when one night it caught fire near the essence tanks, and burned to the ground, several of the men had very narrow escapes and five of the Americans lost all their blankets.

Night work at a triage on the main Verdun road was now being taken up every other night, in addition to the labor of evacuating from Vadelaincourt, which meant long runs to Froidos, Chaumont, and sometimes Révigny, all, however, interesting in their way.

On April 8th, Frank Gailor ("Bishop") left us to the regret of everybody. "Bish" was one of the most popular men of the Section and told most interesting stories of his work in Belgium at the beginning of the war, when he was a member of the Relief Committee. What his "farewell party" lacked in elaborateness was made up for in the sincere feelings of regret which each man felt.

After eating in our "lean-to" by the manure heap for three weeks, the same French doctor, already mentioned, offered us, as our dining-room, the use of a spare tent which was erected in the field opposite the aviation field. The kitchen, too, was moved into a small tent which was rigged up between two pine trees a few feet from the dining-tent. A table in the form of a "T" was built, and with the addition of a set of shelves, known as the "American Bar," built in one corner, everybody was satisfied with our prandial arrangements. "Bishop" Gailor's farewell party, by the way, occurred in these new quarters, and also took the form of a "housewarming," with speeches by Emery Pottle, Graham, Harold Willis and one or two others. A quintet formed with Pottle, Nolan, Graham, Willis, and Seccombe made its initial appearance on this occasion, and the party broke up at a late hour with everybody more or less convinced that he was the next thing to a Caruso.

For a few days thereafter the weather had been ideal, but a change for the worse took place and the old tents had a hard time. There was no work to speak of and everybody spent the day "under canvas" around a small stove indulging in arguments on any sort of subject, while music by Nolan and Graham, on mandolin and guitar, caused the time to pass away agreeably. For three weeks we had nothing but rain, hail, and snow, and as the tent was pretty old, it leaked in many places. The field and side hill was a mass of slimy mud six inches deep, and ten or twelve men were required to push every car into the road.

The weather became better about the first of May, and as the aviators became more active, we got better acquainted with Navarre, Boillot, and Guynemer. This aviation field, by the way, was one of the largest on the whole front and had every type of plane then used by the French. Navarre was then flying a bright red Nieuport and never failed to give a thrilling exhibition whenever he took the air.

On Sunday, May 21, everybody attended an open-air funeral service for the burial of three aviators, one of whom was Boillot. An altar was erected between two trees and the service, which was very impressive, was largely attended by artillery and aviation officers, some three hundred of whom followed the bodies to the cemetery.

The last of the month the fighting grew worse about Fort de Vaux and Fort Douaumont and the Section worked every night and most of the days at the triage.

TO BAR-LE-DUC FOR REPOS --- AIR RAIDS

The 31st found the Section moving to Bar-le-Duc, where it was to be outfitted with new cars and where it was also supposed to be en repos. But as we took the place of and did the work which an English section had been doing, this was far from being a rest, for during the twenty-seven days there, an actual record of 10,500 men carried was one of the things the men pointed to with pride. It meant that a man was on duty fifty-three hours at a stretch, sleeping at one of three places---wherever he was working --- and then going off duty from 1 P.M. until 8.30 the next A.M.

June 10

The second day in town, the Boche planes raided Bar-le-Duc at 1 P.M. and the Section saw some exciting work. There were many narrow escapes in driving round picking up the dead and wounded, Barclay having the closest call when a bomb exploded back of his car and a huge piece went through the body close to his head. Twenty-four planes were counted in all, and 36 dead and 132 wounded were the results. On June 16 and 17, there were two more raids, but they were not so severe as the first one.

Our living quarters at Bar-le-Duc were in an old building built in 1575 and once a monastery, but now used to quarter troops in. The whole edifice was in the form of a square with a large courtyard inside, where were always every night a hundred or more poilus on their way to and from the front. Towards the end of June was a change of French officers, Lieutenant Maas being replaced by Lieutenant Rodocanachi, who became the most popular commander the Section ever had.

At this period, many men used to have lunch with the Lafayette Escadrille, which was stationed just outside of town, where Victor Chapman was killed on the 23d, and, Balsley badly hurt a few days before. Walter Lovell left on June 19 to enter the training school of aviation. He had made a fine Chef de Section and everybody hated to see him go. Oliver Wolcott was made Chef, but was recalled to the States when the Mexican trouble started, and so filled the post only a week.

BACK TO PETIT-MONTHAIRON

June 27 the Section moved back to Petit-Monthairon, where it did evacuation work until September 2, and where we had a small house with sleeping-quarters, dining-room and kitchen, officers' rooms and bureau which were fairly comfortable. There was not much work to do at this moment so several ball games were played with Section Eight and a Norton Section, all of which we lost, with one exception, but which furnished good fun and exercise. Several more new cars and men joined the Section there, J. M. Walker, our new Chef, being among them.

Sections One and Eight were in Dugny part of this time and a certain amount of visiting was done by all the Sections, Section Four, stationed at Ippécourt, sending a few men over to us from time to time. There were big parties on the night of July 4th and again on July 14. Then, too, Powel received a cardboard Victrola with records and gave evening concerts in the "loft," while we had good swimming in the Meuse along with plenty of mosquitoes. On July 29 we received a Hotchkiss workshop car and a new staff car.

On August 6, Mrs. Vanderbilt, who presented each of us with a box of cigarettes, visited the Section for lunch along with Mr. Andrew: everybody was "all dolled up" after spending the whole morning in brushing, polishing, and prinking in general. On September 2, the Section moved to Rampont and took over the postes at Esnes, and Hills 232 and 272, which Section Four had been working.

Section Four taking over the postes between 272 and the Meuse. Five cars were on duty every night, receiving orders at the telephone station at Jouy, three of the cars going to Hill 272 and the others to Esnes or Hill 232. For about ten days the poste in Esnes was the same old ruined château which Section Four had used, when a new poste was established on the outskirts of the town on the road to Béthincourt, where the cars had to run quite a bit farther through the centre of the town over a road full of shell-holes and wreckage off the buildings.

In September the French, in an effort to straighten their line made an attack on the Mort Homme. The artillery barrage started at 5 P.M., and an hour later the infantry "went over." The whole Section had been ordered to Jouy at 6 P.M. and at 7 P.M. the first call came for cars at Hill 272. Shortly after, the rest of the cars were called and we all worked until daybreak carrying in over 250 wounded.

EDWARD NICHOLAS SECCOMBE*

*Of Derby, Connecticut; served six months in S.S.U. Two in 1916; rejoined the Service in November, 1917, and remained in the U.S.A. Ambulance Service during the war.

VII

AT A HOSPITAL

Petit-Monthairon, August 9, 1916

We are quartered in one of the farmhouses belonging to a château, which is now a hospital. You remember, no doubt, the French farmhouses --- a blank wall on the roadside with only an entrance to the courtyard; a dark kitchen, a few bedrooms and a loft, with a few sheds out back. The loft is divided into two parts. We sleep in one of them on stretchers propped up from the floor by boxes or our little army trunks. Some of the boys don't prop up their stretchers, but I find it better to elevate mine, as the rats run all over the floor and incidentally over you if your stretcher rests on the floor. The fleas seem more numerous near the floor, and there are spiders, too. I've been pretty well "bit up." But yesterday I soaked my blankets in petrol and hung them on the line in the courtyard for an airing, so I think I've left the vermin behind. I also sprayed my clothes, especially my underwear, with petrol, which doesn't make much for comfort, except in so far as the animals are baffled. Flies and mosquitoes are abundant, too. We all have mosquito nets which we put over our heads in the evening, making us all look like the proverbial huckleberry pie on the railroad restaurant counter. The poilus around us have adopted our methods, and you see them sitting about looking in the distance for all the world like Arabs. We are better off than the other Sections, though, for our house is very commodious, and near by we have a river to swim in every day. So it is no effort to bathe.

We carry the wounded from the château to the trains. Some trips are about seventeen kilometres one way, and others are more. As the roads are well used, they are rather bumpy; so you have to go very slowly. You can't dash at full speed with wounded. It is slow work, for, in addition to the necessity of making the trip as easy as possible for the blessés, you have to dodge in and out among the transports, which usually fill up the roads. There is a steady stream going and coming --- horses, mules, and auto-trucks.

I never saw so many --- thousands of each kind. Then there is no lagging or loafing; you blow your whistle and the driver of what is ahead of you gives you six inches of road, you squeeze through and take a chance that the nigh mule on the team coming the other way does n't kick. You well know how dusty the roads are. But we have to drive right ahead regardless of it; so you can imagine what sights we are when we get back to our farmhouse --- scarecrows, each one. The dust is powdery and comes off easily, however, so one can get comfortable in a short time.

The blessés are a quiet lot, especially after you give them cigarettes. I always pass around the cigarettes before starting, for then I'm sure those en arrière will be still. Every now and then you have a "humming-bird," that is, a blessé who is so hurt that the least jar pains him and he moans or yells. You can't help him any, so you just have to put up with it. However, I don't like "humming-birds," for you feel, when you are carrying them, that you hit more bumps than you really do.

THE POILU'S AMATEUR THEATRICALS

I went the other day to a show in Trayon where some of the troops are en repos. It was wonderful, for there, right within range of the Boche guns, the French soldiers were giving one of the best musical performances I have ever seen. Among the performers --- men who only a little while before had been in the trenches --- were professional musicians, singers, and actors. It was not amateurish at all; in fact, it was highly professional. The theatre was fitted up more or less like the stage at the Hasty Pudding Club of Harvard. There was an amateurish back-drop, however; but everything else savored of the real Parisian touch. Among the audience were generals, colonels, underofficers, poilus, and five of us. We were invited, inasmuch as we had lent some of our uniforms for the actors. I saw my cap walk out on the stage on a fellow with a little head, so it did n't even rest on his ears, but rather on his nose. The soldiers who could not get in thronged the courtyard and cheered after every song or orchestra piece. The orchestra was made up of everything in a city orchestra, including a leader with a baton. You see each regiment is bound to have professional men in it and they get up these shows. On the whole, it was one of the most impressive sights I've seen, and on top of it all, there was a continuous firing in the near distance. Imagine it, if you can!

We have a cook and a servant, --- one of the poilus who is quartered here, too, and who earns a few sous on the side by serving us, --- also a French lieutenant who is really the head of the Section, a maréchal des logis, and a few other French retainers. They sleep in the same loft with us, and every night they chatter very late, kid each other about the fish they caught or did not catch in the river during the day, laugh and giggle at each other just like children. They are awfully amusing. By the way, all the poilus who are en repos fish, although there are only minnows in the streams about here. To-day I asked several how many they caught, and they said they were only fishing to pass the time. It seems to be a great diversion, for they all do it. Besides fishing the poilus en repos trap foxes, hedgehogs, rabbits, and other animals and then train them. Over across the road in one of the courtyards are two of the cutest little foxes I have ever seen, which play around and are just like little collies until we show up, when they scamper off and get behind a box or a stove and blink at us. We tried to buy one of them, but the owners are too fond of them to let them go.

They all bathe, too, every day --- the poilus. We go in with them, the mules, and the horses. Probably somewhere else in the same river the Boches are bathing. Such is life. We are extremely lucky to get a chance to wash at all and I'm afraid when we move from here --- for we shall soon be moved to poste duty --- we shan't have the comforts we are now enjoying.

I'll write again soon, but now I'm going to bed, --- that is, roll up in my blankets on my stretcher, for there is an early call for to-morrow morning, which means getting your machines over to the château at six o'clock, all ready for the day's work. It's great fun and I am awfully glad to be here. Moreover, there is a satisfaction in knowing that you are helping and that the French are very appreciative, from the poilu up to the highest officers.

CHARLES BAIRD, JR.*

*Of New York; Harvard, '11 ; served in both Sections Two and Three; the above extracts are from letters.

VIII

IN AND AROUND VERDUN

Petit-Monthairon, July 23, 1916

Here we are in this quiet little French village. We move something over a hundred sick and wounded men a day from one hospital to another, or to the hospital trains that take them out of the military zone. I don't find the occupation trying. The men we carry have had hospital treatment and most of them are not in extreme pain; a fact that makes it easier for the drivers when the road is rough, as it generally is. The road service, however, is really excellent. Gangs of men are breaking stones all the time and steam-rollers crushing the stones into smooth hard highways. But the traffic is so enormous that it's only a week or two before the road is worn into little ridges, much like the waves in Florentine paintings.

The dust makes an added complication in driving. A convoy of camions raises a cloud of dust through which you can't see for five minutes after they have passed. This slows us up, for it makes it dangerous to cut around slow-moving vehicles. Even on your own side of the road you are n't entirely safe. To-day I was running along when out of the dust, perhaps twenty feet in front of me, I saw the radiator of a truck. Legally, I would have been justified in keeping on; but he was shut in by a forage convoy; so I did n't stay to argue the matter, but took to the fields, blessing the lightness of my car which made it possible for me to negotiate a pile of road material and a cultivated field.

I am getting quite blasé to the sights of the road, --- paying little attention to ammunition trains or soldiers on the march; but I still slow down when an aeroplane rises near me or when a fair-sized bunch of German prisoners go by.

September, 1916

Went up to my poste de secours with my orderly. It was a mean night, gray and dark. We started early so as to get a little twilight and ran about a mile. Then I heard the whistle of a punctured tire. By the time we had that fixed it was really dark. Nevertheless we went the next mile to the central poste (Jouy) without trouble. Here we waited.

It is a dull place ---a little tiny village, headquarters for our division; after eight-thirty, no lights allowed in the streets or showing from the windows. One of our cars is always there on piquet duty. The two drivers of this car were playing checkers inside their ambulance by candle light. We watched them for awhile, then we went into the poste, which is merely a recording and telephone centre. The sergeant on duty sat at a desk reading a French novel. Another man was at one end of a bench with "Alice in Wonderland." He did n't do it from choice, he explained, but because he could n't find any other book in camp which he did n't know through and through. I sat on the other end of the bench and did exercises in French subjunctives.

A little after midnight a 'phone call for a car at Esnes came in. We were rather hoping it wouldn't, for it had begun to rain very hard outside, and it was impossible to see your hand before your face. However, we went out and got started. It was n't so terribly hard, though our eyes ached from the strain of constantly trying to see what we could n't possibly see. But we got along up the hill and along the level, passing innumerable artillery teams. It was hard to make out the road here and I was glad when I saw a gleam of light ahead and heard the clink of harness. I thought it was a driver lighting his pipe and steered for the light. In a minute my companion yelled and jumped; and my right wheel dropped down. I had run over a wall at the side of the road and my front axle was resting on the ground and the whole car was so canted that there seemed every chance of its toppling over at any moment. On investigation I found that the light I had seen was by the edge of an artillery caisson which had gone all the way down the bank!

We could n't do much by ourselves, but some teamsters came along and joined us heartily as French soldiers always do. We were really too few for the job, but we lifted with all our might and actually did get the car back in the road again. So we once more drove on in the rain, creeping ahead at low speed, however. I remembered the road pretty well from the night before, and finally pulled into our poste (Esnes). Luckily our wounded were n't so badly off and were able to sit up. We started back, passing long lines of soldiers returning from the trenches, who were very spooky in the black. But a minute or so later my right wheel dropped into a shell-hole where a big obus had just exploded. I was glad there were plenty of soldiers at hand. All of these who could find fingerhold lifted and the car pulled out. It seemed incredible but nothing was broken.

We got along slowly after that without accident. About two miles from the poste central it began to rain torrents and we could see nothing. It took real resolution to push on. I've seldom been so relieved over anything as when we made out dimly the houses of the village. From there on to the sorting hospital (Claires Chesnes) we could use lights and my one flickering gas burner seemed fairly to blaze. It had taken us three hours to do twenty miles.

Fromeréville, October

I went up and got three men with no more trouble than dropping both rear wheels in a shell-hole as I turned around; but I got some poilus to push me out and returned to headquarters about 2 A.M. However, I had n't much more than gone to sleep before there was a 'phone call for Marre, which, is a long way over dark and lonely roads. I wallowed through a number of shallow shell-holes, turning over one spring-hanger thus pushing the body against one wheel and creating a contact brake, bad for the tire. Leaving the poste I dropped two wheels into a shell-hole and had to get my blessés out and have them help push. About halfway to the poste I ran out of gas. I put in a gallon from my reserve, and when I had got it in, found from the smell that it was kerosene. We were not far from a French battery and the road was fairly pock-marked with shell-holes; so, although there were no shells coming in at the time, I thought it better not to stay there, and ran on on the kerosene. You can do it on low speed, apparently. I got down to headquarters absolutely dead tired. Now I am home again also dead tired.

Later

I've seen any number of regiments on the march and never yet heard the men singing or the bands playing. In Paris this may seem a little cold and uninterested, but here where the real work is done it is wonderfully impressive --- suggestive of endless determination and reserve strength. Now, determination and reserve strength without hysteria is just what France is showing. I am the more struck with this because severe fighting is going on close to us and I have been in the midst of the wounded coming into the big evacuation hospital. There were n't enough ambulances to go around and great crowds, with bloody bandaged heads and arms, came in the big motor trucks that carry the soldiers up to the line. All last night I saw them coming in, grim and suffering and uncomplaining. It was one of the great uplifting experiences of my life. I have seen nothing to match it for sheer courage, moral as well as physical. There is n't the rawest, most provincial driver in our work who has n't expressed the most unqualified admiration for the French poilus. Certainly, as I looked at them last night, they seemed to me sane, entirely sane men, terribly brave and unbeatable.

The rumors are that the victory was impressive and that Fort Douaumont is ours again. It's a fine achievement if true; but that seems less important to me now than the spirit I've seen. Out here at the front one does n't worry about the French Army.

JOHN R. FISHER*

*Of Arlington, Vermont; Columbia; entered the Service in May, 1916, and a year later was put in charge of the organizing of the Field Service Training Camp at May-en-Multien. Later Mr. Fisher became Captain in the U.S.A. Ambulance Service.

IX

THE LAST DAYS OF THE BATTLE OF VERDUN

Rampont (near Verdun), October 6, 1916

We are located here in the woods, overlooking Rampont, between Sainte-Ménehould and Verdun, near Nixeville, and about twelve miles from Le Mort Homme, Hill 304 and Hill 272. Already I have had some wonderful experiences during these three weeks at Verdun. During the attack a fortnight ago, we certainly had a time of it. In addition, the loss of Kelley and the injuries to Sanders, of Section Four, over at their poste at Marre, was a terrible tragedy to us. Both boys I knew and talked with only a few days before the affair happened.

The attack lasted three nights, and we had many interesting adventures. The main stunt is to keep on the road. Out of eighteen cars, four were "in bad"; either their drivers tried to climb trees or walls, or else supply wagons with excited drivers kept to the middle of the road, and, of course, side-swiped the little Ford into a ditch. Seccombe and Struby managed to ditch their cars nicely. Iselin had a most wonderful "stunt" with his. After climbing an embankment, it fell over on its side, all four wheels in the air; but to our amazement, it "chugged" off nicely when righted by a dozen husky poilus, always ready to help Americans. Well, I had a little difficulty myself finding the road, as I had made previously only one trip up to 272, which is about twelve miles; and without lights on the dark highways, with much traffic going up and returning, it is sometimes by pure luck that a fellow gets by.

Many drivers as well as their horses get excited, and when passing "Dead-Man's Turn" and "Shell-Hole-Hollow" everybody has steam up. In addition, when half the route has been gone over, the batteries are at our rear, so that, with the racket from the trucks, the roar of the guns, and the whistling of the shells through the heavens, it certainly does seem as though hell were let loose. Then, too, the landscape all about us is so desolate! Montzéville and Esnes are terribly shot up --- trees cut down, not a house standing complete, and debris filling the streets; so that in a general state of depression our thoughts continually rest on our tires, expecting at any moment a blow-out, which means a half-hour's job in the "God-forsaken burg," as we call it.

I have had an interesting "twenty-four hours"' service, which proved to be thirty-six hours, during these few days that our division has been en repos. We were kept on the go, each making 300 kilometres. Our two cars made several trips to the many surrounding towns between here and Vaubécourt, Révigny, and Bar-le-Duc. Back here far behind the lines, it is quite a pleasure to be able to drive at night with lights. Révigny, by the way, is approached via the Argonne --- a picturesque country it is still, though there are the many destroyed villages and towns, and farms dotted with graves of the fallen heroes of the Marne.

The other night it was raining in torrents when I struck Bar at 1 A.M., with one malade, a victim of a mad dog's bite. Much to my surprise the entrée pour malades was apparently closed, so there was nothing for me to do but climb up over the parapet, Jean Valjean style, and rouse the sleepy brancardier, who hastily opened the porte, and then I made my get-away in the long trip back to Rampont, some fifty-five kilometres.

It is a great life, full of interesting happenings here with the soldiers; long trips, including many irregular and unexpected daily episodes; sometimes eating at camp, often at a field hospital kitchen; always finding a way out of a tight fix, even though for a moment all looks black; while things are made all the better by the fact that we have some bully good fellows here, the spirit and the work of the squad being such that it is a great satisfaction to be a member thereof.

Neuilly, December 13, 1916

On October 23 last, during a bombardment in a French village, Fromeréville, I was hit in the leg by a fragment of a shell which exploded a few feet in front of my car. Fortunately the car was empty, as I had just returned from a trip to the field hospital, and was turning about to load up again at the poste de secours. Fortunately, too, the éclat did not fracture the bone. Quickly stopping the car, which was but a few minutes, away from an abri whither I managed to crawl, the doctors applied a bandage, and a few minutes later I was on a stretcher. Afterwards I was informed that two brancardiers were killed and eight of us in the town wounded. Mine was the only car on duty at the moment of the bombardment as my comrade had left sometime before on a call to a village ten kilometres back. After three weeks at the small field hospital, during which time the piece of shell was extracted, I was brought to our hospital, the American Ambulance here at Neuilly, where I am making such progress that I am trusting to resume active service with my Section at Verdun very soon, if by the will of God I am able.

WILLIAM H. C. WALKER*

* Of Hingham, Massachusetts; enlisted in the Field Service, December, 1915; became a member of Section Two, at Pont-à-Mousson; wounded at Verdun, October, 1916; left the Field Service, August, 1917, and enlisted in the Canadian Field Artillery; honorably discharged from the Canadian Forces, December, 1917, in consequence of physical disability.

X

MUD AND RATS AT RAMPONT

Until November 8, the Section continued to wallow in the mud of Rampont, and it was "some mud." It clung in great clots to our shoes, thence to our puttees, our overcoats and to everything we possessed, including ourselves. It was on this date that we packed up and moved to Ville-sur-Cousances, where, for living quarters, we had barracks, large and airy; so airy in fact that we soon found that our beds were the only warm places. The "General" clung to his tent which he pitched off to the cast in the windiest place he could find, and yet managed to keep himself warmer than any one else in the outfit; and five o'clock always brought a hungry crowd to his tent-flap clamoring to be admitted for tea. These barracks would have been passable enough had we been the only creatures present, but we were far from being alone in our glory. Rats were our rivals; rats of all sizes, small, large, fat and thin. They were present in ever-increasing numbers, making our days doleful with discoveries of half-eaten cakes of chocolate, biscuits, and cheeses, and our nights hideous with an uproar that sounded like Charlie Chaplin in a tin-can factory. Olympic games were their specialty, followed by social dinners at the Ritz, as MacIntyre's store of supplies might have been aptly termed.

Our postes remained the same, Marre and Hill 272. The weather also remained the same, --- rain, sleet, snow and high winds. Roads were about the only thing that changed and they grew worse and worse. Because of the bad weather we had plenty of work to do, --- ten cars on duty regularly with extra cars on call and frequently the White truck. Under the circumstances, Diemer, the American mechanic, and Saintot, the French mechanic, were kept busy changing broken rear axles, broken rear springs, broken front springs, broken radiators, bent mud-guards, and all other parts that came in contact with foreign bodies on dark, rainy nights. The crowning achievement of these mechanics was the changing of an entire rear axle at Marre, in the pitch darkness of a rainy night, without a single light to help them, as Marre was exactly six hundred yards from the Boche lines and of course no lights could be used.

MORT HOMME --- GLORIEUX --- LA GRANGE-AUX-BOIS

On December 28, the Boches "pulled off" an attack on the Mort Homme which kept us fairly busy for one night; but outside of that there was little to note other than the routine work, during which we were looked after with infinite kindness by the non-commissioned officers of the G.B.D., who, every morning at 3 A.M., at Marre, shared with us drivers a five-course dinner, --- and a very welcome meal it was, after a long night's work. At Fromeréville, whatever they had was ours and we were as members of a large family. These are things which none of us will ever forget.

On January 10 the Section moved for a short repos to barracks at Glorieux, and had perhaps two or three calls a day to camps where the different regiments of the division were located; but the greater part of our time was spent in Verdun walking about the city.

On January 19, 1917, we again packed up our ever-increasing and never-decreasing baggage and fled over icy roads to La Grange-aux-Bois in the Argonne, where we were allotted two large rooms, one good, the other bad.

The Section being divided at this time into two squads, it was quite obvious that one squad would inevitably draw the poor room, and as violent argument seemed imminent, the "General" and Harry Iselin decided to flip a coin for it. Much to our disgust, the "General," with true British nonchalance, lost the toss, and those of us who were in his squad started out immediately to locate other and better quarters. Most of us were successful --- Conquest, Struby, Heilbuth, and I getting palatial chambers with electric lights and a southern exposure. Without boasting I should say that we had discovered the Fifth Avenue of La Grange-aux-Bois. MacIntyre and Wheeler contented themselves with what might possibly be called Madison Avenue, while the "General," Bigelow and MacLaughlan --- and I make this statement with no reservations of any kind whatsoever --- lived in a snug little rat-infested attic on the Bowery.

WORK IN THE ARGONNE

From this time on our life was an easy one. We had only two main postes, one up in the woods, Sept Fontaines --- later changed to Chardon, the other in a beautiful valley at the Abbaye de Chalade. For the first few days we worked another poste, Le Chalet, nearer the lines, but the Germans as usual became most unpleasant and nearly "finished off " several of our cars as well as several of our drivers.

As there was practically no work here, it was decided to send cars there only on call from La Chalade, with the immediate result that there were no more close "squeaks,"---at least not for some time. The Boches picked a quarrel with La Chalade and shelled the district intermittently, but beyond planting a few shells in the buildings and peppering one car with éclats, succeeded in doing no damage. During our five months' rest cure in the Argonne, the only casualty suffered by the Section occurred in the afternoon of April 25, when Raymond Whitney was bitten in an unmentionable part of his anatomy by a large black dog. This severe wound was cauterized at the hospital amidst the cheers of the assembled drivers.

As the spring advanced, rumor as to our leaving the Argonne followed rumor. First we were to go to Saint-Mihiel, then to the Champagne, and finally- we were relieved by Section Nineteen, which arrived on May 25th when we were put en repos to await further orders.

JOHN E. BOIT*

*Of Brookline, Massachusetts; Harvard, '12; joined Section Two in May, 1916; became Sous-Chef; subsequently was a First Lieutenant, U.S.A. Ambulance Service.

XI

THE SUMMER OF 1917

From La Grange-aux-Bois we were ordered to Dombasle-en-Argonne; and great was the rejoicing; for after five months of inactivity and monotony, the prospect of active service was a pleasant one. We reached Dombasle on June 25 without incident, and after turning out Section Fifteen, took up their quarters in a large building at the edge of the town. They had fixed up the place to the nth degree of comfort, with a shower-bath, garden, pavilion, and in fact all the modern conveniences. Hence it was with a well-satisfied air and an anticipatory smile that we settled down in what seemed the best quarters we had ever had. Before Section Fifteen left, the members assured us of "easy work" and a "quiet time enjoyed by all," and left us to the working out of our own damnation.

THE EX-VILLAGE OF ESNES

There is no use describing the ex-village of Esnes to those members of the Field Service who have seen it; and as a corollary, there is no use in describing it to those members of the Service who have not seen it, for they have had it described to them ad infinitum and ad nauseam. Suffice it to say that Esnes was our poste and it lay under the Côte 304 and in full view of the Mort Homme --- and the seeing was fairly good in those days. We have never yet found out whether our friends of Section Fifteen were amusing themselves at our expense or not, about the prophesied "quiet time" which we were to have there. Anyway, shortly after our arrival we found ourselves in the midst of one of the nicest little parties ever given on the Verdun front, and there are those who claim that they have seen "some parties" on said front. It seems that the Boches had been meditating the prospective taking-back of various portions of Côte 304 which they had lost previously and elected June 29 as the most propitious time to try to do so. Whatever faults the Boche may or may not have, and we do not claim that he is without them, one of them was not to let things stagnate on the Verdun front. So for the next three days we had ten cars continuously on duty, and what is more, they were running continuously.

This at the front. Meanwhile, events at the rear were not entirely devoid of interest. The Section, or rather the part of it which was not up at the poste was at supper when something suspiciously like an arrivée was heard in the immediate vicinity. The "older" men looked at one another, the rookies looked at the "General," who went on with his soup. A second came in, still closer; then a third which knocked the plaster from the ceiling, a generous piece of which fell in the "General's" soup. He rose, calmly looked round and muttered, "Well, I'll be damned," --- and left those parts. He did n't run, for that would have been undignified, but he simply left --- and he was n't the last to reach the shelter of a neighboring and friendly haystack some hundred yards off out in the open. --

We moved camp that night with never a sigh for our late palatial and very unhealthy quarters. What with Boche attacks and French counter-attacks, we found little time to do anything but eat, sleep, and work, and for the entire period from June 29 until July 18, when our Division, the 73d, finally ended that particular chapter of Verdun history by making one big and very successful attack, retaking all the ground which had been lost and taking many prisoners, the Section did all the evacuations for these several attacks and won for itself a Divisional Citation --- the second from this Division.

THE DEATH OF HARMON CRAIG

For us, the most tragic part of the whole summer came on July 15, when Harmon Craig was killed at Dombasle. After having gone over some of the worst stretches of road in the whole sector for three weeks with a smile on his face and a jest on his lips, he was wounded at his poste, by the side of his car while it was being loaded, and died six hours later as bravely as he had lived. He was buried in the cemetery back of Ville-sur-Cousances, and as he was laid to rest, the guns behind Montzéville, roaring out a last farewell, sped the 73d over the top to avenge him.

A PEACEFUL REPOS AT LIGNY-EN-BARROIS

On July 23 we received our orders to leave, and with as much joy as we had arrived a month before, we packed up, and after a last visit to Craig's grave, set out for Nançois-le-Grand, a village of several hundred inhabitants seven kilometres from Ligny-en-Barrois, where we arrived, after a dusty run of several hours.

The quiet of the little town was as grateful to our nerves as the beauty of the surrounding country to our eyes, accustomed to desolation. After a month of hard work, it was good to lie in our cars, for we lived in our cars, which were drawn up in a field, happy in the assurance that five or ten of us would n't have to hurry up to the front and after thinking great calm thoughts, serve the best interests of the country by drifting off to sleep, not to awaken until 10.30 the next morning. It was good to lie under the trees and meditate, or simply to lie under the trees. It was good to stroll in the dusk and finally wind up a perfect day with a perfect omelette. In short, it was Paradise!

Then after a week of this pastoral life, as the charms of the succulent omelette gave way to those of the fragrant grape, wine and wassail became the order of the day. Who can adequately describe the farewell parties of Walker, or do justice to the entertaining which Whitney furnished on that occasion? Who can describe the farewell parties of Whitney and Whytlaw and the eloquent farewell speeches, made on these occasions, or the still more eloquent responses by MacIntyre, that "prince of bon vivants"? What pen could picture the joys of whympus hunts, commenced precisely at 12.01 P.M.; Of crap games commencing at reveille (10.30 A.M.) and lasting until taps (12.30 A.M.); of swimming parties in the canal, which invariably ended at the Café de la Meuse at Tronville? Who can declare our elation at the decoration of Whitney, Ames, and the "Mec," a condition of affairs which naturally called for another party? And finally, how can we relate how deeply our hearts were touched when we found that our cars had been decorated by the girls of the village as the short weeks of repos came to a close on August 16?

We left for Sommaisne that day, and I think we may say with truth that our departure was regretted by the entire village; certainly we regretted departing, and look back on those five short weeks as on a pleasant dream of golden sunshine, green hills, and France in summertime. We remained at Sommaisne three days, after which we followed our new Division, the 48th, to Souhesme.

HENRY D. M. SHERRERD*

*Of Haddonfield, New Jersey; Princeton, '17; enlisted in the Field Service in May, 1917; served in the U.S.A. Ambulance Service until the end of the war.

XII

IN LINE AT VERDUN

Ville-sur-Cousances, Thursday, June 28, 1917

We were now brought face to face with the reality of the coming offensive, and began to appreciate on what an enormous and terrifying scale a modern attack is carried out. As soon as we reached the main road we came upon an endless line of camions all rumbling along in the darkness, each filled with infantry to its uttermost capacity, the men being jammed in like cattle. There were also guns, huge guns such as I have never seen in the Argonne. For three hours we kept passing this solemn parade of men and cannon. At each cross-road were stationed officers and sentinels with shrouded lanterns who directed and urged on the procession. Most of the men were riding in silence, many even managing to sleep in their awkward positions; but occasionally we passed a camion whose crew was chanting some weird song of war or love. I am told that this concentration of men has been going on for many days. Here at Cousances the whole atmosphere is impregnated with the vague imminence of an approaching offensive.

This region is totally different from the Argonne where we were before. The country is barren and deserted and the fields of stubble stretch for miles along the white and dusty roads. The sun is burning everything and the thick white alkali dust gives all objects a gray and withered appearance. We no longer see the beautiful rich green of the Argonne vegetation. Everything seems baked and dead. Every three or four miles one comes upon a small ruined village, now deserted. The whole region has been blasted by shells; nowhere does the country fail to remind one of the terrible struggle that has been going on for so long in this sector. Cousances, itself nothing but a group of wrecked houses, is quite close to the front, and there is certainly much more activity here than in our former sector.

Putting it literally, this Section was baptized in fire as soon as it reached here, for to-night about eight-thirty a despatch-rider came tearing up to the bureau on his motor-cycle and said that the Boches were attacking at Hill 304. So instantly we began to hustle around and prepare for heavy work.

Harper and I were the first to leave, he being the driver and myself orderly. As we passed out of Cousances we saw several artillery field pieces hurrying up the road toward the first lines, and later passed two battalions of the 346th drawn up by the roadside and ready to be sent ahead. A heavy rain was falling and frequent flashes of lightning lit up the country; but the night was not very dark and we had little difficulty in keeping on the road, which is well screened all the way. But of course we could not use any lights. French batteries on both sides of us were firing steadily, and the whistle of the departing shells was incessant; but we heard no Boche shells coming in. At the poste we found the Lieutenant hurriedly giving directions to the fellows, and heard that the French were to counter-attack at daybreak.

HELL'S CORNER

No blessés had come in as yet but many were expected. Before long Whytlaw came down with a load and Harper and I started up to relieve him. I had heard a lot about the danger of this poste, and in no detail was it exaggerated. The road is covered with stones which have been hurriedly thrown into shell-holes, and there were also many new holes which had not been filled in. For over a mile after making "Hell's Corner" we are in plain sight of the Boche trenches. We can see their star shells start from the ground, and it seems as if they exploded directly over our heads. The road is being shelled all the time but one can never go fast on account of the danger of these shell-holes. We passed trucks, and some squads of infantry which were difficult to see in the darkness. By this time the din of the cannonading was terrific and the bursting of the Boche shells occurred at no very comfortable distance.

The road grew worse and worse, and finally it became almost impassable. I doubt if any car but a Ford could ever make that trip at night. I did n't go sightseeing at all, but having reached our destination, made a fairly straight line toward the abri, where we learned that Bixby's car had just been smashed by a shell while standing in the yard and would be useless for the rest of the night. We were also told that the Boches had just dropped in some gas bombs, and we were ordered to be sure that our masks were in readiness. Ray and I, the first to go back after having a brief smoke in the shelter of the abri, carried an assis and two couchés. We breathed a lot more easily after once gaining "Hell's Corner," and accomplished the rest of the trip without mishap. It was after two when we got back here. But as a counter-attack was expected we had to await word and be ready to start out again any minute. So both of us simply crawled into our car and managed to fall asleep very easily. We slept soundly until the Lieutenant woke us and told us to go to bed as we probably shouldn't be needed.

HEAVY WORK DURING AN ATTACK

Sunday, July 1

It is now three days since the attack commenced and it appears to be still going on. There are Boche attacks and then French counter-attacks, then artillery duels, and then more attacks. As close as we are to the lines, we know very little of what happens, or who is winning. The losses have been terrible on both sides, but this does not mean that the attacks have failed. Our Section has been working at a terrific pace. I am so tired that the events of the past few days seem all confused and even unreal. It is such a wonderful relief to be sitting way back here in perfect safety and with no responsibilities that I feel as if I had just recovered from a long sickness. I slept quite late Friday after the hard work of the night before, and after rising had little to do for the rest of the day; both sides had ceased activities for the time, and we heard but little firing until evening. But we were warned to be prepared for a large dose at night, as the French were scheduled to attempt a rush on their lost positions.

About 6.30, just after the dinner gong had rung and as I was leaving my room, there was suddenly a "swish-bang" and a big shell exploded on the opposite side of the road, about fifty yards from our headquarters. Of course I flopped on the ground as soon as I heard the warning whistle, and then rising, proceeded with more or less undignified hustle for the abri under our main building. Everybody else thought of the very same place and joined in the general stampede. In about three minutes another came in and we could hear the éclats flying about outside and clipping pieces of stone off the houses. After a few more shells the Boches let up on us for awhile and we went upstairs and began dinner. But we had n't finished our soup before they started dropping again, the first one so startling us that we spilled more or less soup around the room. We continued eating, however, until suddenly there was a terrific explosion followed by a horrible crunching sound of falling bricks and plaster. A shell larger than the others had struck the house, or what remained of the house, directly opposite our building. It would have been foolish for us to remain where we were, because our building, already tottering from the effects of many shellings, might bury us alive if one of those big marmites ever landed squarely on it. The abri was also a dangerous place, being very poorly made and liable to cave in upon us. The safest place, therefore, was out doors; so we all streaked for a field which was well removed from all the crumbling foundations which made up this village and which are ready to fall almost from the mere concussion of a large shell. We gathered behind a large haystack where already several others had collected, and waited. The shells came in regularly, every once in a while striking some building and reducing it to still further ruin. One landed about thirty yards from the big tent where twenty of us sleep and we later found over a dozen rips in the canvas, some big enough to admit one's body. No shells came near enough, however, to do any damage; but at every explosion one had to lie flat in order to avoid the flying éclats.

At seven-fifteen, the time set for those on duty to start for the poste, the shells were coming in about every minute. So there was nothing to do but to streak for our cars which were in front of the main building, near which the majority of the shells were landing, and to make as quick a get-away as possible. The "General", and Reed left first and the last we saw of them they were hurrying very ungracefully over the rough field to where the cars were, about 250 yards away. The Lieutenant then told Newcomb and myself to get ready and to leave as soon as the next shell landed. So we lined up as if we were runners waiting for the sound of the starting pistol, and, as soon as the "R-R-ang" came, in we legged it. One shell came in while we were running and we both went down on our bellies. We gained the house before the next one landed and then waited for it. It came in too close for comfort and then I went out and cranked my car while Newcomb ran back to his shack for his coat.

Just as I got the motor started I received one of the biggest scares of my life. A shell came in and burst so close that I thought surely it had me. I was just getting into the car and so could not flop. I was hit by the flying earth and falling stones thrown up by the shell, which struck the car in several places, one piece even striking and glancing off my helmet. Newcomb, who then appeared, looked surprised to see me still alive; and before the next shell landed, we were well down the road and both joined in a long-drawn-out sigh of genuine relief.

The French attack had now fairly commenced and on all sides of us the batteries were pounding away. Not for a moment did the screeching of shells and the roaring of guns cease. At one point John Ames and I clambered up on a ruined house and took a look over the country. It was a view I shall never forget. Our task is comparatively small, and we are prepared to do it faithfully. Nine cars are lined up ready to cover the attack, and the drivers and their orderlies stand waiting orders. The Lieutenant is here directing us and planning the shifts and reliefs.

The road which we have to go over is the most damnable stretch I have ever known. As fast as the old shell-holes are filled in with stones, new ones are made. As we drive along in the darkness, straining our eyes to keep the car out of holes and ditches, the noise of the French batteries and German shells is deafening. Far down the road we see a flash followed by a roar. It is German shrapnel and we crouch instinctively in our seats as we realize that in another minute we shall be passing over that spot. In back of us is an explosion and flying rocks and earth are scattered about the slowly moving car. We can't go faster because of the condition of the road, although instinct cries out to us to open the throttle and streak for our destination. We plod slowly along, trying to talk unconcernedly and longing for the termination of the ride.

We pass through the town and enter the driveway of a fallen château, the cellar of which is now used for a poste de secours. This driveway is about fifty yards long. To look at it one would say it was impassable, but over those rocks and stones and through the shell-holes we go. This is the most dangerous place of all, and so often do the shells fall that no one ever ventures out to repair the road. We have to slow down practically to a standstill, and crawl and bump our way along. How I hate the sight of this place. It is all so cruel and relentless --- the wrecked houses, the torn-up roads, and the huge shell-holes, some of the older ones half filled with stagnant water. Here and there a wagon which has been struck sprawled by the roadside. It is a scene of sickening desolation.

I made the first trip to Esnes with Newcomb as orderly. It had not yet grown dark, so we easily passed by the shell-holes. When we reached Esnes we had to take our gas-masks from their cases and wear them about our necks, ready to put them on when passing through the gassed area. They served us well, and in less than two minutes we could remove them and breathe fresh air again, but our eyes burned from the poisonous fumes. The odor of the stuff left us horribly depressed. It has a sickeningly sweet smell like that of over-ripe fruit and makes one's lungs feel as if some heavy weight had been imposed on them.